The following letter was written to Will Jones by his younger brother, Cliff, from a military hospital in October 1916, shortly after he had been wounded on the Somme. He had been hit in the leg and the wrist after “going over the top” with his Grenadier Guards platoon on the first day of the Battle of Morval. Promoted to sergeant, he survived the war, only to die of meningitis in 1926.

Cliff Jones (left)

Cliff Jones (left)20242 L/Cpl C.M. Jones, 1st GG.

F.I. Ward,

Queen Marys Military Hospital, Whatley,

Lancashire

4/10/16

Dear Will,

Thanks very much for your letter dated 30/9/16, which I received yesterday. (Mon.) Yes I am sure you should feel glad, rather than otherwise to know I am in England, I am nearly off my head with joy to be away from that fearful place in France, and when I see the awful gashes which some poor fellows have, I cannot term my wounds, as anything but slight, it is really a miracle how I escaped. You say you want a long newsy letter, well if I can possibly remember, I will describe to you what happened to me from the time I was at Church Service on the Sunday, the 24th until I reached St Mary’s here in Lancs. Well to begin with we had a very touching service in “Trones Wood”, just about 2 miles behind the actual firing line, or it might have been less, and I don’t quite know what the matter with me but I had a lump rise in my throat, and also my eyes become rather wet, but at any rate we finished the service about eleven o’clock, and the next thing was “dinner” bully and biscuits.

Dressing station at Trones Wood under fire

After dinner the Sergt of our sapping platoon called us out on parade and made a list of ammunition which we should have to carry into action with us:- 3 Bombs & 220 rounds per man. He then sent me in charge of 8 men to draw this Ammunition from a dump about a mile away. When I returned I handed over the Ammo, to the Sergt, and went back to the shell hole, where my kit was to have a rest as we were going into the trenches that night to prepare for the advance next day. It appears that whilst I was on this fatigue in the afternoon the Sapping officer had given the platoon a lecture on how we were going to go on in the advance and what we were to do, well of course I did not know anything about that until later on. The officer, at the end of the lecture warned the platoon to parade at 9.30 p.m. and I and the 8 men who was on the fatigue thought we were parading with the Batt at eleven o’clock. Well we had some rum served out to us at 9 p.m. and I had just settled down again after drinking my rum when I heard someone shout “Cpl Jones”, I answered “Hallo” and the man shouted that the platoon was on parade waiting to move to the trenches. That did it, I got up and was on prde in about two shakes and had a good chewing off by the Sergt, but he sang a bit small when the officer came along and asked him if he had told us what time to parade. He tried to shuffle out of it but the officer wouldn’t let him “Did you warn these men what time to parade.” The Sergt replied “No Sir, not your time.” And then you should have heard the officer let drive, my word a decent navvy would turn green with envy to hear it

The communication trench up which Cliff Jones passed after being wounded

The communication trench up which Cliff Jones passed after being wounded

Well we started off and on the way we had to pick up some ammunition, 10 boxes, 1,000 rds in each box, and two men to carry each box, we were allright so far, but worse was to come, we went on and presently found ourselves on a main road leading up to “Ginchy”, but at the same time it led us right away from the position we had to take up, and the officer did not know it until we had gone about a mile out of our way, and when at last we found our way, we saw the Batt just going into the trenches, so that we had been wandering about for an hour and a half. We followed behind the Batt and eventually we reached our position, which was a trench just behind our second line, which had been dug by us about two nights before. After making ourselves as comfortable as possible under the circumstances we laid down in the bottom of the trench to get some sleep if possible. The next morning the bombardment was supposed to start at 9 and keep on until 12 noon when our 4th Batt and the 2nd Scots were to go over and take the German front line, and from there on and take the second, and then the 1st Grens had to pass right through and take the third line and a village “Le Boeufs”, perhaps you can find it on the map I think it is on the left of Combles. Well, I have told you what was mapped out, now I will tell you what did happen as far as I can. About 9 oclock our heavy guns started raining shells over on to what seemed to me to be the German reserve lines, but beyond that I did not notice anything out of the ordinary until about 12.15 p.m. when the whole of our artillery started sending a barrage fire over, and the Germans replied and I can tell you it was like hell let loose. Well we waited about a quarter of an hour, before we went over, as our work is to follow the Batt and consolidate the positions as they are taken.

British troops going over the top at the Battle of Morval

The word was passed down: “Get ready to go over,” and a few minutes after the officer blew his whistle and over we went. We went over in two partys the officer and myself with one party and the Sergt and another Cpl with the other. On our left was the 1st Div and on our right was the Welsh Gds. After we got over the top we advanced through the most terrible machine gun and shrapnel fire it is possible to imagine, and it is marvellous how any man possibly got through it untouched. We passed over our 2nd line, and then over our front line before I felt anything and then I felt a stinging sensation in my left thigh, when I looked I found a three cornered tare (sic) in my trousers. I went on thinking it was a bit of dirt had touched me, the next thing I saw was our officer with a part of his hand blown away, but he did not stop, he went on shouting “Come on, come on,” and the next thing, I caught one bang through my wrist, and then my trouble commenced. As soon as I was hit I dropped into a shell-hole, and as luck would have it, there was a fellow in the hole that was in the same squad as myself at Caterham. I shouted “Hallo Jack” he replied “Hallo Jones where are you hit” I told him and he bound up my wound, and then we both went out from hole to hole as best we could until we reached the communication trench, and then we had to go through it, of course communication trenches are just what the Germans shell more than anything else, and we had whizz-bangs, big black shrapnell and every kind of shell bursting all around us in fact I could feel the heat of them, but it seemed as if we had some super-natural protection over us, as we came out safely when we had got back by “Guillemont” and “Ginchy”. I met two officers who were in charge of the “Land tanks”, those armoured cars you have read about, and they stopped me, and a Cpl of the 2nd Batt GG who was coming back with me, to ask us how things were going on, so we told him we had reached the 2nd objective and I asked him he could give us a drink of rum as we felt done up, well as a matter fact I could hardly get along by myself, so the officer said he would give us a drink, and pulled out a half-pint flask of rum, and we had a drink each, which put new life into us.

"Those armoured cars you have read about." Tanks.

"Those armoured cars you have read about." Tanks.

We went on until we reached “Trones wood” where there was a Soldiers Club which provided hot tea and cake and cigs for the wounded only, so we had a little refreshment there and went to a dressing station near by and was dressed and sent on in motor lorries near “Happy Valley” where we were enochulated (sic) and sent to a place called “Groovetown” by train. We stopped there the night and then were sent on by train to “Eataples”. By the way, at Groove town while I was waiting to see the doctor, I heard someone say “Halloa Whacky” and when I looked round I saw to my surprise Cpl Evans who has been one of my closest chums ever since I went to France. Just fancy we went out with the same draft, slept together we were in the same platoon up to about a couple of months ago, and we got wounded in the same fight, and we are now occupying the next bed to one another in this hospital. But I am afraid I shall have to leave here before he does as his wounds are worse than mine:- shrapnell in the shoulder, but I suppose I must be thankful for small mercies. To go on with the yarn, when we arrived at Eataples we were taken from the station to the hospital in char-a-bancs and got straight to bed after a splendid supper. The next morning we had a hot steam bath with a cold shower afterwards, and I can tell you we enjoyed it A.1. We then had to go before the doctor to know whether we were for blighty or Convalescent Camp. I went in and the doctor told the orderly to shave my arm, and then he wrote on my card, destination England. I cant describe my feelings when I saw it at any rate you can bet I was more than glad. Well it was Friday morning when we reached Calais by train from Eataples and there we took the boat for Dover, and I enjoyed the crossing very much. When we reached Dover I hung on to try to get in a London train, but they only sent Officers and Colonials to London, so I had to put up with Lancs, and I find it is allright here, the only thing is we cant get any writing materials, so should be glad if you would send me on a pad. It is a pity about the watch, but as you say someone may return it but I shouldn’t expect it if I were you. I received the cigarettes and note for 10/- quite safe, I will write Mr Goddard as soon as I can. I don’t think it would be worth your while to come up as it would cost too much, and as I shall have ten days leave later on I think it would be waste of money so don’t do it. I am afraid I shall have to stop now, I shall be able to tell you more about it later on. No I have not kept that Diary, perhaps you don’t know that it is a crime in the Army to keep a diary? We had an exhibition here on Sat about 7,000 people came and there were dummy trenches on view 3d a time dancing in the evening, and simply ached to start but my slippers werent suitable. Well old chap I must dry up as it is nearly dinnertime so give my love to all,

Yours affec,

Cliff

P.S. I have just received the shaving kit;- Celmax safety razor, Brush and Soap, many thanks for the same, if you show this to Mr Goddard and he wants to put it in a report, tell him to leave out the part I have underlined and put in brackets.

The forge at Newbury. The man in the left foreground with the axe is John Marchant Jones.

The forge at Newbury. The man in the left foreground with the axe is John Marchant Jones.

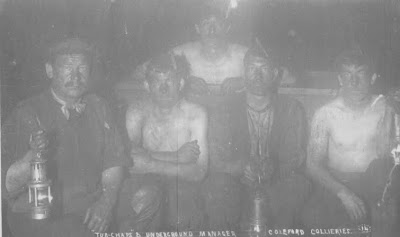

Notice in the above picture that the man on the left is wearing the notorious guss and crook, a harness which passed under his crutch to draw a "putt", a sledge laden with coal.

Notice in the above picture that the man on the left is wearing the notorious guss and crook, a harness which passed under his crutch to draw a "putt", a sledge laden with coal.

Sadly Will Jones was no sentimentalist. When he acquired the Newbury pit yard after the Second World War for his concrete block business, he wiped all his priceless glass negative plates and used them to repair the windows in the buildings!

Sadly Will Jones was no sentimentalist. When he acquired the Newbury pit yard after the Second World War for his concrete block business, he wiped all his priceless glass negative plates and used them to repair the windows in the buildings!

I walked eastwards down the High Street in search of Brook Cottage, the house where he had grown up with his parents, John and Millicent, and his three brothers and two sisters. It wasn’t difficult to find. On the corner of the street and a little lane, it was announced by a wooden sign, next to a post box let into the wall of the house.

I walked eastwards down the High Street in search of Brook Cottage, the house where he had grown up with his parents, John and Millicent, and his three brothers and two sisters. It wasn’t difficult to find. On the corner of the street and a little lane, it was announced by a wooden sign, next to a post box let into the wall of the house. “Cottage”, for its place and period, is something of a misnomer. Brook Cottage is quite a substantial house, and John Marchant Jones and his bride, Millicent Martin, must have been considered a fortunate young couple when they went to live there after their marriage. There was money on both sides of the match, from John’s adoptive mother, Mrs Hobday Jones of “Camden House”, and from Millicent’s father, Benjamin Martin, a mining surveyor and Coleford’s parish clerk.

“Cottage”, for its place and period, is something of a misnomer. Brook Cottage is quite a substantial house, and John Marchant Jones and his bride, Millicent Martin, must have been considered a fortunate young couple when they went to live there after their marriage. There was money on both sides of the match, from John’s adoptive mother, Mrs Hobday Jones of “Camden House”, and from Millicent’s father, Benjamin Martin, a mining surveyor and Coleford’s parish clerk.  I stood in the street and wondered how the family, with such a promising start, could have foundered so spectacularly, reduced to hand-outs of bread and tea from the parish. The handsome, dashing, John Marchant Jones perhaps was no better than he should have been, and one family legend tells that Millicent was pregnant when she went up the aisle of Holy Trinity church. On the other side of the street to Brook Cottage stands the old Temperance Hall, now a private house but still with an improving text from the Book of Habakkuk over the door. Was it the demon drink that sank my great grandfather?

I stood in the street and wondered how the family, with such a promising start, could have foundered so spectacularly, reduced to hand-outs of bread and tea from the parish. The handsome, dashing, John Marchant Jones perhaps was no better than he should have been, and one family legend tells that Millicent was pregnant when she went up the aisle of Holy Trinity church. On the other side of the street to Brook Cottage stands the old Temperance Hall, now a private house but still with an improving text from the Book of Habakkuk over the door. Was it the demon drink that sank my great grandfather? I walked on, through the trees and up through a field, wondering if this might have been the way Will Jones had taken to his work at the colliery. He said later in life that he loathed the work, particularly on the “batches”, the heaps of smoking slag and spoil. I had no idea if any trace of Mackintosh, closed for some ninety years, still existed. As I topped a rise, I could see a hillock covered in trees in front of me. A new farm lane had been driven around it, cutting back the soil around its base – except it wasn’t soil. Even from a distance the blue-black sheen of slag was obvious. Here was the old batch of the Mackintosh colliery, where Will Jones had toiled at sorting scraps of coal from the waste.

I walked on, through the trees and up through a field, wondering if this might have been the way Will Jones had taken to his work at the colliery. He said later in life that he loathed the work, particularly on the “batches”, the heaps of smoking slag and spoil. I had no idea if any trace of Mackintosh, closed for some ninety years, still existed. As I topped a rise, I could see a hillock covered in trees in front of me. A new farm lane had been driven around it, cutting back the soil around its base – except it wasn’t soil. Even from a distance the blue-black sheen of slag was obvious. Here was the old batch of the Mackintosh colliery, where Will Jones had toiled at sorting scraps of coal from the waste.

That brick archway once had led to the top of the shaft, beneath the winding tower, where my grandfather had banged shut the cage doors on the squatting pitmen before they were lowered seven hundred dizzy feet below the ground.

That brick archway once had led to the top of the shaft, beneath the winding tower, where my grandfather had banged shut the cage doors on the squatting pitmen before they were lowered seven hundred dizzy feet below the ground. The yard today is a sprawling mass of buildings and works, owned by the Vobster Cast Stone Company. The receptionist kindly sought permission for me to wander around the site. The tall building which once housed the Cornish Beam Engine to pump the water out of the pit galleries still survives.

The yard today is a sprawling mass of buildings and works, owned by the Vobster Cast Stone Company. The receptionist kindly sought permission for me to wander around the site. The tall building which once housed the Cornish Beam Engine to pump the water out of the pit galleries still survives. Near to it stood my grandfather’s original offices, built in his own blocks and now abandoned.

Near to it stood my grandfather’s original offices, built in his own blocks and now abandoned. I regained the footpath which took me round the edge of the site through woodland thick with the scent of the buddleia which run riot there. Where the yard ended, a hard path ran away eastwards.

I regained the footpath which took me round the edge of the site through woodland thick with the scent of the buddleia which run riot there. Where the yard ended, a hard path ran away eastwards. This was the track of the old railway which connected Newbury and Mackintosh with the sidings at Mells Road. The track is bordered by fields, and above it stands a handsome building, Page House, and below it the vale which leads to Vobster.

This was the track of the old railway which connected Newbury and Mackintosh with the sidings at Mells Road. The track is bordered by fields, and above it stands a handsome building, Page House, and below it the vale which leads to Vobster.

Eventually the track became a metalled lane at Upper Vobster Farm and a little further on, at St Edmund’s House, I turned down a path into the fields. At a stile into a road, I turned right and walked down into the hamlet of Vobster.

Eventually the track became a metalled lane at Upper Vobster Farm and a little further on, at St Edmund’s House, I turned down a path into the fields. At a stile into a road, I turned right and walked down into the hamlet of Vobster. You may be forgiven, however, for claiming that the Vobster Inn was the model of the “King William” in my grandfather’s books. After all, he spent every evening possible in the place, putting the world to rights with his pals.

You may be forgiven, however, for claiming that the Vobster Inn was the model of the “King William” in my grandfather’s books. After all, he spent every evening possible in the place, putting the world to rights with his pals. He wouldn’t recognise the pub today. I hadn’t been through the door since he died, and felt completely disorientated until I realised that the old front door had disappeared, and that I had entered by the side of the building. An old photograph on the wall of the bar was there to remind me of how things had been, and part of the room was signed as “George’s Snug”, while another board declared this area of the bar to be the “Village Parliament”. Was it merely coincidence that this recalled the title of Will Jones’s last book, “Our Village Parliament”? I took one look at the very young, and very pretty, girl behind the bar, and decided to keep my memories to myself. The “Vobster” – the inn bit gets dropped in some of its publicity – is more restaurant than pub these days but that’s the reality of making a living from a boozer today. Pints of cider and hours of chat and whist wouldn’t pay many bills. I had a good pint of Butcombe bitter, a pricey cheese sandwich, and some of the best chips I have ever tasted, arranged in a little vase for all the world like a bunch of flowers.

He wouldn’t recognise the pub today. I hadn’t been through the door since he died, and felt completely disorientated until I realised that the old front door had disappeared, and that I had entered by the side of the building. An old photograph on the wall of the bar was there to remind me of how things had been, and part of the room was signed as “George’s Snug”, while another board declared this area of the bar to be the “Village Parliament”. Was it merely coincidence that this recalled the title of Will Jones’s last book, “Our Village Parliament”? I took one look at the very young, and very pretty, girl behind the bar, and decided to keep my memories to myself. The “Vobster” – the inn bit gets dropped in some of its publicity – is more restaurant than pub these days but that’s the reality of making a living from a boozer today. Pints of cider and hours of chat and whist wouldn’t pay many bills. I had a good pint of Butcombe bitter, a pricey cheese sandwich, and some of the best chips I have ever tasted, arranged in a little vase for all the world like a bunch of flowers. I walked past some cottages along the road towards Coleford and then climbed a stile on the left of the road into a field. I took a path to the left which led to a bridge across the Mells Stream.

I walked past some cottages along the road towards Coleford and then climbed a stile on the left of the road into a field. I took a path to the left which led to a bridge across the Mells Stream. There was a flash of blue over the water downstream – a kingfisher! “A spell is wov’n by Somerset,” wrote grandfather, and he must have loved this country between Coleford and Vobster. Even so, as the path took me westwards, there was evidence that even here the pits had left their mark. A stone building standing apparently without purpose in the middle of a field had been part of the Vobster colliery, and some old low arches half-concealed by nettles in woodland further on might have been remains of the coke ovens which existed here.

There was a flash of blue over the water downstream – a kingfisher! “A spell is wov’n by Somerset,” wrote grandfather, and he must have loved this country between Coleford and Vobster. Even so, as the path took me westwards, there was evidence that even here the pits had left their mark. A stone building standing apparently without purpose in the middle of a field had been part of the Vobster colliery, and some old low arches half-concealed by nettles in woodland further on might have been remains of the coke ovens which existed here.

Half way along the valley leading back to Coleford are some coarse fishing lakes. I walked round and round them, sweating in a waterproof coat and slouch hat as the thunder banged about me, without finding the path which should have taken me to Hippy’s Farm. After half an hour of this, I gave up and got south of the lakes to take a well-defined path westwards, despite a stile installed by the local ramblers which promised far more than it delivered.

Half way along the valley leading back to Coleford are some coarse fishing lakes. I walked round and round them, sweating in a waterproof coat and slouch hat as the thunder banged about me, without finding the path which should have taken me to Hippy’s Farm. After half an hour of this, I gave up and got south of the lakes to take a well-defined path westwards, despite a stile installed by the local ramblers which promised far more than it delivered. The buildings of Coleford were now visible on the ridge to the north and, like some sinister watchtower, above the trees loomed the top of my grandfather’s house, “Mendip Ho!” Sadly, darkness of the gathering storm made it impossible to photograph, but later the present owner of the house very kindly gave me permission to take pictures from his garden. Where my grandfather had his eyrie on the flat roof, there is now a proper penthouse.

The buildings of Coleford were now visible on the ridge to the north and, like some sinister watchtower, above the trees loomed the top of my grandfather’s house, “Mendip Ho!” Sadly, darkness of the gathering storm made it impossible to photograph, but later the present owner of the house very kindly gave me permission to take pictures from his garden. Where my grandfather had his eyrie on the flat roof, there is now a proper penthouse. The views from the house remain completely unspoilt. From here at least you can see the “Springfield” countryside of his imagination.

The views from the house remain completely unspoilt. From here at least you can see the “Springfield” countryside of his imagination. I walked into Coleford past the “King’s Head”. Even today Coleford boasts three pubs, a legacy of the thirsty miners who once drank in the village. Just above it I came across Camden House where John Marchant Jones had lived when he first came from London to Coleford as the adopted son of Hannah Hobday Jones. Hannah, the widow of a cabinet maker in Camden Town, North London, had returned to her native Coleford to start a shop at Camden House, the name which the property bears to this day.

I walked into Coleford past the “King’s Head”. Even today Coleford boasts three pubs, a legacy of the thirsty miners who once drank in the village. Just above it I came across Camden House where John Marchant Jones had lived when he first came from London to Coleford as the adopted son of Hannah Hobday Jones. Hannah, the widow of a cabinet maker in Camden Town, North London, had returned to her native Coleford to start a shop at Camden House, the name which the property bears to this day. Climbing a steep hill, I came to Holy Trinity Church, opposite to the old Miner’s Welfare Institute which Will Jones bought and gave to the village as a church hall. In the church is the controversial window designed by Keith New which Will presented. There is a plaque in Will’s memory below the window, now sadly darkened by the growth of the trees outside.

Climbing a steep hill, I came to Holy Trinity Church, opposite to the old Miner’s Welfare Institute which Will Jones bought and gave to the village as a church hall. In the church is the controversial window designed by Keith New which Will presented. There is a plaque in Will’s memory below the window, now sadly darkened by the growth of the trees outside. On the northern edge of the churchyard is the group of family graves, including those of Benjamin Martin and his wife, and John Marchant and Millicent Jones, the latter’s’ memorial placed there by their eldest son many years after their passing.

On the northern edge of the churchyard is the group of family graves, including those of Benjamin Martin and his wife, and John Marchant and Millicent Jones, the latter’s’ memorial placed there by their eldest son many years after their passing.

Below the church and the hall stands the old National School, now a youth centre but not much changed since the Jones boys were photographed there in the 1890’s.

Below the church and the hall stands the old National School, now a youth centre but not much changed since the Jones boys were photographed there in the 1890’s.

Keith New described his work in the “Coleford Parish Paper” of October 1958 thus. “The subject is taken from I Samuel xix 9-10: ‘And the evil spirit from the Lord was upon Saul as he sat in his house with his javelin in his hand: and David played with his harp. And Saul sought to smite David even to the wall with the javelin; but he slipped away out of Saul’s presence, and he smote the javelin into the wall: and David fled, and escaped that night.’

Keith New described his work in the “Coleford Parish Paper” of October 1958 thus. “The subject is taken from I Samuel xix 9-10: ‘And the evil spirit from the Lord was upon Saul as he sat in his house with his javelin in his hand: and David played with his harp. And Saul sought to smite David even to the wall with the javelin; but he slipped away out of Saul’s presence, and he smote the javelin into the wall: and David fled, and escaped that night.’ In the same issue the vicar, Father John Sutters, did his best to justify the radicalism of the window to a sceptical congregation. “ For most of us in Coleford this window is a completely new experience, to which time will be needed to adjust ourselves. To begin with, it is stained, not just painted, as are our other windows, and so the colours are deeper and heavier. In the second place, in the central figures and the details of the background the artist has not been content simply to copy the stock ideas of what things and people look like to which we have grown used, but has expressed what the story of Saul and David means to him in the style of a young artist of 1958. But I think that the greatest shock for most of us, as we look at this window, is to realize that the Bible story, like whatever else deals with the whole of human nature, has to face the hideous wickedness of which human beings are capable. That, after all, is what the Crucifix has to tell us, if we were not hardened by seeing it so often. People often want to find comfort and soothing in Church: we like pretty-pretty pictures, soft sugary hymn-tunes, nothing to make us think or to stir us up; we want an escape from the harshness of life into a dream-world. But the religion of the Bible, and the Church, the religion of our Lord Jesus Christ, has to face and deal with ugliness and wickedness, not to ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist.

In the same issue the vicar, Father John Sutters, did his best to justify the radicalism of the window to a sceptical congregation. “ For most of us in Coleford this window is a completely new experience, to which time will be needed to adjust ourselves. To begin with, it is stained, not just painted, as are our other windows, and so the colours are deeper and heavier. In the second place, in the central figures and the details of the background the artist has not been content simply to copy the stock ideas of what things and people look like to which we have grown used, but has expressed what the story of Saul and David means to him in the style of a young artist of 1958. But I think that the greatest shock for most of us, as we look at this window, is to realize that the Bible story, like whatever else deals with the whole of human nature, has to face the hideous wickedness of which human beings are capable. That, after all, is what the Crucifix has to tell us, if we were not hardened by seeing it so often. People often want to find comfort and soothing in Church: we like pretty-pretty pictures, soft sugary hymn-tunes, nothing to make us think or to stir us up; we want an escape from the harshness of life into a dream-world. But the religion of the Bible, and the Church, the religion of our Lord Jesus Christ, has to face and deal with ugliness and wickedness, not to ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist. By the early 1960’s the Miners’ Welfare Institute was redundant. All the pits had closed, and the social needs of the area were well-served by the lavishly-appointed Coleford British Legion Club, opened in 1956. In its early years the Club’s weekend dances provided a popular battleground for some memorable punch-ups between gangs of lads from Pensford and from Peasedown.

By the early 1960’s the Miners’ Welfare Institute was redundant. All the pits had closed, and the social needs of the area were well-served by the lavishly-appointed Coleford British Legion Club, opened in 1956. In its early years the Club’s weekend dances provided a popular battleground for some memorable punch-ups between gangs of lads from Pensford and from Peasedown.